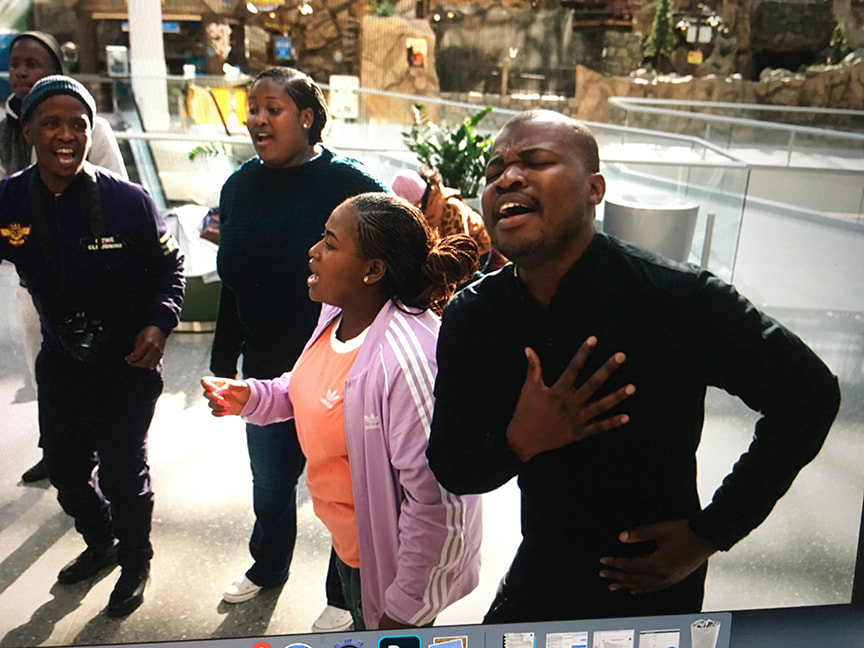

"I feel like I'm home again," South African choir visits MinnesotaAfter a 2018 trip to South Africa, the Minnesota Chorale welcomes the Gauteng Choristers for a series of concerts.

Photos by Leila Navidi

NOVEMBER 14, 2019 — 9:06AM

Enjoy this beautiful photo story from Leila Navidi at the Star Tribune

http://www.startribune.com/i-feel-like-i-m-home-again-south-african-choir-visits-minnesota/564873982/

Photos by Leila Navidi

NOVEMBER 14, 2019 — 9:06AM

Enjoy this beautiful photo story from Leila Navidi at the Star Tribune

http://www.startribune.com/i-feel-like-i-m-home-again-south-african-choir-visits-minnesota/564873982/

REVIEW: Paul McCreesh leads Minnesota Orchestra, Minnesota Chorale in an exhilarating concert

By Rob Hubbard | Special to the Star Tribune

PUBLISHED: April 1, 2023

Perhaps what Twin Cities classical music lovers wanted this weekend was a celebration of spring. What with the Minnesota Orchestra performing Joseph Haydn's quintessential paean to fresh beginnings, "The Creation," it seemed a chance to exult in the coming of birdsong and budding trees, flowers and flowing streams.

Ah, but nature had other ideas. On Friday evening, Orchestra Hall was about only one-third full for a performance of Haydn's magnum opus, presumably because of the multiple inches of heavy, wet snow that started falling about an hour before the concert. Yes, a blizzard was predicted and it's understandable if ticket holders decided that one more storm was just one too many to face this winter.

Hopefully, they traded their tickets for Saturday's final offering of "The Creation," because Friday's was the most enjoyable Minnesota Orchestra concert this season. Led by English conductor Paul McCreesh (who also translated the oratorio's text), it was as big and bold an interpretation as one could wish for a work that's basically about the beginning of everything. With three excellent vocal soloists and the Minnesota Chorale's singers throwing themselves wholeheartedly into the work's celebratory spirit, it was an evening overflowing with exhilaration.

It seemed appropriate that nature should crash this party, for it is indeed the guest of honor in Haydn's oratorio. Splicing the creation story from the biblical book of Genesis with embellishments on the tale from John Milton's "Paradise Lost," the text is something of a summoning to mindfulness, a suggestion to observe what's around us — the land, the water, the birds, the stars, even the worms and bugs — and pause to offer gratitude.

No, more than that: To delight in it. And this interpretation of "The Creation" was all about delight. It was there in how the Minnesota Orchestra musicians imitated the sounds of our natural environs or tapped into the score's ebullient joy. And in the ideal combination of technical skill and obvious affection for the material displayed by the three solo singers.

Add to this the Minnesota Chorale energetically embracing the role that Haydn wrote for the choir in this work: placing a full-voiced exclamation point on each chapter of the Judeo-Christian creation story.

The vocal soloists' shining moments were plentiful. Soprano Joélle Harvey displayed a voice of strength and subtlety, at its most arresting when singing the praises of birds and acting as Eve, even when she had to deliver some eye-rolling text about the rewards of obedience.

REVIEW: Powerful pieces build one of most memorable concert experiences in 2019

By Rob Hubbard | Special to the Pioneer Press

PUBLISHED: November 14, 2019 at 3:59 pm | UPDATED: November 14, 2019 at 5:47 pmWhy haven’t I heard this before? Audience members at Thursday’s Minnesota Orchestra concert may have asked themselves that while filing out of Minneapolis’ Orchestra Hall.

They’d just experienced a powerful performance of a moving musical work, Ralph Vaughan Williams’ “Dona Nobis Pacem,” a 45-minute epic cantata for orchestra, choir and two vocal soloists. The orchestra was joined not only by the Minnesota Chorale, but singers with whom it collaborated on its 2018 tour of South Africa, the Gauteng Choristers and 29:11, as well as two vocal soloists, one South African, the other American.

It proved an awe-inspiring experience, a profoundly heartfelt reflection on the price of war and the value of life. Capping a program that included the U.S. premiere of a new cello concerto by one of the most distinctively voiced of contemporary composers, Australia’s Brett Dean, and a brief but very rewarding encounter with the music of Jean Sibelius that conductor Osmo Vanska and the orchestra play so well, it proved one of the most memorable concerts Twin Cities audiences will experience in 2019.

So why is it that you probably haven’t heard of this “Dona Nobis Pacem” from the pen of a 20th-century English composer best known for such involving works as “Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis” and “The Lark Ascending”? Well, when it premiered in 1936, the rise of fascism had Europe on edge about the prospect of impending war.

Vaughan Williams remained marked by his experiences as an ambulance driver during World War I, and he set out to fashion a large-scale plea for peace. But a text and music that convey the ugliness of war, the common humanity of the victorious and defeated, and the ensuing inescapable grief surely came to be considered the opposite of an armed forces recruiting call when German bombs starting falling on England. It didn’t fit with the tenor of the times and is seldom heard today.

Thank goodness that the Minnesota Chorale’s artistic director, Kathy Saltzman Romey, pitched it to the Minnesota Orchestra as an ideal vehicle for a collaboration with their South African colleagues. Thursday’s midday concert confirmed it to be a compelling evocation of the conflicting spirits of peace and warfare.

The contrast was never more gripping than when South African soprano Goitsemang Lehobye’s urgent pleas for peace stood defiantly after the drums of war had fallen away. Or when bass-baritone Dashon Burton sang of death with both strength and gentleness. For me, the attempted sense of triumph in the work’s final movement felt forced and not nearly as impactful as the sadness expressed in most of the piece (Vaughan Williams’ issue, not the performers’). But it lands in a sad, soft place that should touch even the hardest of hearts.

By Rob Hubbard | Special to the Star Tribune

PUBLISHED: April 1, 2023

Perhaps what Twin Cities classical music lovers wanted this weekend was a celebration of spring. What with the Minnesota Orchestra performing Joseph Haydn's quintessential paean to fresh beginnings, "The Creation," it seemed a chance to exult in the coming of birdsong and budding trees, flowers and flowing streams.

Ah, but nature had other ideas. On Friday evening, Orchestra Hall was about only one-third full for a performance of Haydn's magnum opus, presumably because of the multiple inches of heavy, wet snow that started falling about an hour before the concert. Yes, a blizzard was predicted and it's understandable if ticket holders decided that one more storm was just one too many to face this winter.

Hopefully, they traded their tickets for Saturday's final offering of "The Creation," because Friday's was the most enjoyable Minnesota Orchestra concert this season. Led by English conductor Paul McCreesh (who also translated the oratorio's text), it was as big and bold an interpretation as one could wish for a work that's basically about the beginning of everything. With three excellent vocal soloists and the Minnesota Chorale's singers throwing themselves wholeheartedly into the work's celebratory spirit, it was an evening overflowing with exhilaration.

It seemed appropriate that nature should crash this party, for it is indeed the guest of honor in Haydn's oratorio. Splicing the creation story from the biblical book of Genesis with embellishments on the tale from John Milton's "Paradise Lost," the text is something of a summoning to mindfulness, a suggestion to observe what's around us — the land, the water, the birds, the stars, even the worms and bugs — and pause to offer gratitude.

No, more than that: To delight in it. And this interpretation of "The Creation" was all about delight. It was there in how the Minnesota Orchestra musicians imitated the sounds of our natural environs or tapped into the score's ebullient joy. And in the ideal combination of technical skill and obvious affection for the material displayed by the three solo singers.

Add to this the Minnesota Chorale energetically embracing the role that Haydn wrote for the choir in this work: placing a full-voiced exclamation point on each chapter of the Judeo-Christian creation story.

The vocal soloists' shining moments were plentiful. Soprano Joélle Harvey displayed a voice of strength and subtlety, at its most arresting when singing the praises of birds and acting as Eve, even when she had to deliver some eye-rolling text about the rewards of obedience.

REVIEW: Powerful pieces build one of most memorable concert experiences in 2019

By Rob Hubbard | Special to the Pioneer Press

PUBLISHED: November 14, 2019 at 3:59 pm | UPDATED: November 14, 2019 at 5:47 pmWhy haven’t I heard this before? Audience members at Thursday’s Minnesota Orchestra concert may have asked themselves that while filing out of Minneapolis’ Orchestra Hall.

They’d just experienced a powerful performance of a moving musical work, Ralph Vaughan Williams’ “Dona Nobis Pacem,” a 45-minute epic cantata for orchestra, choir and two vocal soloists. The orchestra was joined not only by the Minnesota Chorale, but singers with whom it collaborated on its 2018 tour of South Africa, the Gauteng Choristers and 29:11, as well as two vocal soloists, one South African, the other American.

It proved an awe-inspiring experience, a profoundly heartfelt reflection on the price of war and the value of life. Capping a program that included the U.S. premiere of a new cello concerto by one of the most distinctively voiced of contemporary composers, Australia’s Brett Dean, and a brief but very rewarding encounter with the music of Jean Sibelius that conductor Osmo Vanska and the orchestra play so well, it proved one of the most memorable concerts Twin Cities audiences will experience in 2019.

So why is it that you probably haven’t heard of this “Dona Nobis Pacem” from the pen of a 20th-century English composer best known for such involving works as “Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis” and “The Lark Ascending”? Well, when it premiered in 1936, the rise of fascism had Europe on edge about the prospect of impending war.

Vaughan Williams remained marked by his experiences as an ambulance driver during World War I, and he set out to fashion a large-scale plea for peace. But a text and music that convey the ugliness of war, the common humanity of the victorious and defeated, and the ensuing inescapable grief surely came to be considered the opposite of an armed forces recruiting call when German bombs starting falling on England. It didn’t fit with the tenor of the times and is seldom heard today.

Thank goodness that the Minnesota Chorale’s artistic director, Kathy Saltzman Romey, pitched it to the Minnesota Orchestra as an ideal vehicle for a collaboration with their South African colleagues. Thursday’s midday concert confirmed it to be a compelling evocation of the conflicting spirits of peace and warfare.

The contrast was never more gripping than when South African soprano Goitsemang Lehobye’s urgent pleas for peace stood defiantly after the drums of war had fallen away. Or when bass-baritone Dashon Burton sang of death with both strength and gentleness. For me, the attempted sense of triumph in the work’s final movement felt forced and not nearly as impactful as the sadness expressed in most of the piece (Vaughan Williams’ issue, not the performers’). But it lands in a sad, soft place that should touch even the hardest of hearts.

Think choral music is bland? Minnesota Orchestra concert may blow your mindInternational cast presents "La Pasión" as the finale of Minnesota Orchestra's Sommerfest.

By Jenna Ross Star Tribune

AUGUST 1, 2019 — 11:36AM

"La Pasión según San Marcos" is such an epic work — performed so rarely — that if Ahmed Anzaldúa had heard about it being staged in Los Angeles, he would have flown there. No question.

So the fact that it's being performed here in Minnesota is exciting. The fact that Anzaldúa is preparing the chorus for this weekend's performances?

Exciting and terrifying.

"I haven't slept much in the last week," he said.

For two months, Anzaldúa, a Minnesota-based, Mexico-born choral conductor, has been prepping Minnesotans to sing Argentine composer Osvaldo Golijov's theatrical reimagining of the Bach Passions, a 90-minute piece steeped in Afro-Cuban, Brazilian and other Latin American musical styles.

"La Pasión según San Marcos," or "The Passion According to St. Mark," has only been staged some 54 times — almost always by the Venezuelan choir that premiered the work in 2000: Schola Cantorum de Venezuela. Twenty-five members of that choir were supposed to trek to Minnesota, pairing up with singers of the Minnesota Chorale and Border CrosSing to perform with the Minnesota Orchestra on Friday and Saturday. But because of the crisis in their country, the singers couldn't get the passports and visas required to travel here for the crowning concerts of this year's Sommerfest.

CLICK HERE for the balance of the article

By Jenna Ross Star Tribune

AUGUST 1, 2019 — 11:36AM

"La Pasión según San Marcos" is such an epic work — performed so rarely — that if Ahmed Anzaldúa had heard about it being staged in Los Angeles, he would have flown there. No question.

So the fact that it's being performed here in Minnesota is exciting. The fact that Anzaldúa is preparing the chorus for this weekend's performances?

Exciting and terrifying.

"I haven't slept much in the last week," he said.

For two months, Anzaldúa, a Minnesota-based, Mexico-born choral conductor, has been prepping Minnesotans to sing Argentine composer Osvaldo Golijov's theatrical reimagining of the Bach Passions, a 90-minute piece steeped in Afro-Cuban, Brazilian and other Latin American musical styles.

"La Pasión según San Marcos," or "The Passion According to St. Mark," has only been staged some 54 times — almost always by the Venezuelan choir that premiered the work in 2000: Schola Cantorum de Venezuela. Twenty-five members of that choir were supposed to trek to Minnesota, pairing up with singers of the Minnesota Chorale and Border CrosSing to perform with the Minnesota Orchestra on Friday and Saturday. But because of the crisis in their country, the singers couldn't get the passports and visas required to travel here for the crowning concerts of this year's Sommerfest.

CLICK HERE for the balance of the article

Review: Mahler – Symphony No. 2 (“Resurrection”) – Osmo Vänskä, Minnesota Orchestra

Tal Agam - February 7, 2019

This is the third and, to me, the most successful in Osmo Vänskä’s ongoing Mahler cycle with the Minnesota Orchestra. Together with other ongoing Mahler cycles – namely Adam Fischer’s Dusseldorf series and Daniel Harding newer cycle with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra – we can sense a trend emerges of playing direct, no-nonsense Mahler that frees itself from self indulgence and treating the score as “classically” as possible, letting the music speak for itself.

CLICK HERE FOR THE BALANCE OF THE ARTICLE

Tal Agam - February 7, 2019

This is the third and, to me, the most successful in Osmo Vänskä’s ongoing Mahler cycle with the Minnesota Orchestra. Together with other ongoing Mahler cycles – namely Adam Fischer’s Dusseldorf series and Daniel Harding newer cycle with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra – we can sense a trend emerges of playing direct, no-nonsense Mahler that frees itself from self indulgence and treating the score as “classically” as possible, letting the music speak for itself.

CLICK HERE FOR THE BALANCE OF THE ARTICLE

Leonardo da Vinci comes to life in new work by Minneapolis composer Jocelyn Hagen

Classical Music Features - Garrett Tiedemann · Mar 27, 2019

This weekend, the Minnesota Chorale and the Metropolitan Symphony Orchestrawill present the world premiere of a new work by Minneapolis composer Jocelyn Hagen.

The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci is a seven-movement multimedia experience commissioned jointly by Minnesota Chorale and Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra. The co-premiere is a first for the organizations, which have an extensive performance history together. They have independently performed Hagen's work in the past, including the orchestra's premiere of her work Solar in 2012.

CLICK HERE FOR THE FULL ARTICLE

Classical Music Features - Garrett Tiedemann · Mar 27, 2019

This weekend, the Minnesota Chorale and the Metropolitan Symphony Orchestrawill present the world premiere of a new work by Minneapolis composer Jocelyn Hagen.

The Notebooks of Leonardo da Vinci is a seven-movement multimedia experience commissioned jointly by Minnesota Chorale and Metropolitan Symphony Orchestra. The co-premiere is a first for the organizations, which have an extensive performance history together. They have independently performed Hagen's work in the past, including the orchestra's premiere of her work Solar in 2012.

CLICK HERE FOR THE FULL ARTICLE

Mahler’s Symphony No. 2, Resurrection

“…the [Mahler] series is shaping up to be a defining achievement of [Vänskä’s] Minnesota Orchestra tenure.”

— Terry Blain, Star Tribune, January 31, 2019

"When you hear the lower strings opening the symphony so fiercely and at breakneck speed in Vänskä’s Resurrection you know you’re in for a treat. This is true for the whole performance overall....No matter how many recordings of this symphony one has, this is more than a welcome addition to the Mahler discography.”

— T.A. Konsgaard, The High Arts Review, January 19, 2019

“The Minnesota Chorale is in fine form, singing with outstanding precision and power. Ruby Hughes’ soprano is a gleaming addition.”

– Matthew Richard Martinez, ConcertoNet, January 5, 2019

“…the BIS engineers outdid themselves. This is one of the better recorded Seconds on record, perhaps one of the best recorded Mahler Symphonies, on SACD or the compatible two channels CD.”

— Tal Agam, The Classic Review, February 7, 2019

“…the [Mahler] series is shaping up to be a defining achievement of [Vänskä’s] Minnesota Orchestra tenure.”

— Terry Blain, Star Tribune, January 31, 2019

"When you hear the lower strings opening the symphony so fiercely and at breakneck speed in Vänskä’s Resurrection you know you’re in for a treat. This is true for the whole performance overall....No matter how many recordings of this symphony one has, this is more than a welcome addition to the Mahler discography.”

— T.A. Konsgaard, The High Arts Review, January 19, 2019

“The Minnesota Chorale is in fine form, singing with outstanding precision and power. Ruby Hughes’ soprano is a gleaming addition.”

– Matthew Richard Martinez, ConcertoNet, January 5, 2019

“…the BIS engineers outdid themselves. This is one of the better recorded Seconds on record, perhaps one of the best recorded Mahler Symphonies, on SACD or the compatible two channels CD.”

— Tal Agam, The Classic Review, February 7, 2019

Review: speed kills

by Larry Mellman | Parterre Box

2:57 pm | May 22, 2019

"...Vanska did not conduct this Requiem. Edward Gardner did. I had not previously heard of him but his CV is impressive and his Requiem was beautifully realized, from an opening so hushed it forced the audience to stop fidgeting, to bone-shattering Dies irae, rex tremendae, and every shade in between.

The acoustic of Orchestra Hall is overly bright so the brass easily overwhelms the soundscape, but Gardner balanced his forces with a precise ear and the players responded with lyricism and virtuosity.

Ironically the Requiem delivered all the nuance, style and Verdian line that Traviata lacked. Gardner’s reading was not as sublimely spiritual as Giulini’s, but from the opening pianissimo to the a capella chorus to the vocal solos and ensembles, he found the right tempo and attitude for the music to soar.

The solo quartet, Ailyn Pérez, Elizabeth Deshong, Rene Barbera and Eric Owens, were nicely matched and superbly supported by the formidable Minnesota Chorale at peak pitch..."

by Larry Mellman | Parterre Box

2:57 pm | May 22, 2019

"...Vanska did not conduct this Requiem. Edward Gardner did. I had not previously heard of him but his CV is impressive and his Requiem was beautifully realized, from an opening so hushed it forced the audience to stop fidgeting, to bone-shattering Dies irae, rex tremendae, and every shade in between.

The acoustic of Orchestra Hall is overly bright so the brass easily overwhelms the soundscape, but Gardner balanced his forces with a precise ear and the players responded with lyricism and virtuosity.

Ironically the Requiem delivered all the nuance, style and Verdian line that Traviata lacked. Gardner’s reading was not as sublimely spiritual as Giulini’s, but from the opening pianissimo to the a capella chorus to the vocal solos and ensembles, he found the right tempo and attitude for the music to soar.

The solo quartet, Ailyn Pérez, Elizabeth Deshong, Rene Barbera and Eric Owens, were nicely matched and superbly supported by the formidable Minnesota Chorale at peak pitch..."

Review: Minnesota Orchestra makes opera sound sacred on Verdi’s ‘Requiem’

By Rob Hubbard | Special to the Pioneer Press

May 18, 2019 at 12:29 am

It’s a great month to get to know Giuseppe Verdi, the dominant figure in the history of Italian opera. As Minnesota Opera closes its production of the composer’s most popular opera, “La Traviata,” the Minnesota Orchestra is performing another of his masterpieces, the “Requiem” mass he wrote upon the 1873 death of another giant of Italian culture, the poet and statesman Alessandro Manzoni.

If you have time to catch each this weekend – and, hey, it’s supposed to rain, so why not? – you might just get worn out by all the passion. For Verdi insisted upon that, above all. And Friday evening’s first performance of the “Requiem” at Minneapolis’ Orchestra Hall overflowed with passion. Led by English conductor Edward Gardner, it was a gripping performance, a big, booming look at death that seemed designed both to comfort and to frighten you into repentance.

With the Minnesota Chorale at the top of its game and its voices, this may have been the loudest “Requiem” I’ve ever encountered (and I mean by any composer). Drawing listeners in with its whispering opening, it soon was jarring the audience into alertness with a “Dies Irae” that featured powerful bass drum whacks from principal percussionist Brian Mount, a lovely oboe solo from John Snow, and arias of awe and resignation from bass Eric Owens.

But the most powerful moments came when the audience was summoned into quiet reverence. Such as on an Offertorio with the sweetest of quartets by the four guest vocalists, tenor Rene Barbera upping the operatic ante with a dramatic delivery. The ensuing Sanctus found the Minnesota Chorale (exceptional all evening) doing its best imitation of an opera chorus, especially on the emphatic final notes.

I’d be hard pressed to say who impressed me more, soprano Ailyn Perez or mezzo-soprano Elizabeth DeShong. They wrapped listeners in a blanket of harmony on a duet on the “Agnus Dei,” but that movement showed DeShong at the peak of her powers as she plunged into the depths of her range, sounding very much like a tenor before opening the “Lux Aeterna” with clear, high tones.

Perez then burst forth on the finale, the “Libera Me” that Verdi actually wrote earlier as part of a multi-composer collaborative “Requiem” upon the death of another of opera’s greatest composers, Gioacchino Rossini. When the “Dies Irae” was done offering its shouts of advocacy for fear-based faith, Perez was ready with a transporting, transcendent lullaby. And the Minnesota Chorale – expertly prepared by Kathy Saltzman Romey – seized the standard for drama and passion and ran with it on a final, full-choir fugue.

Verdi’s “Requiem” stands as one of music history’s most powerful hybrids of the sacred and secular, and the enraptured audience greeted its final notes with a lengthy silence suiting the sacred then an extended standing ovation that felt like a cathartic release from the reverie due a very memorable performance.

If You Go

Who: The Minnesota Orchestra with conductor Edward Gardner, soprano Ailyn Perez, mezzo-soprano Elizabeth DeShong, tenor Rene Barbera, bass-baritone Eric Owens and the Minnesota Chorale

What: Giuseppe Verdi’s “Requiem”

When: 8 p.m. Saturday, 2 p.m. Sunday

Where: Orchestra Hall, 1111 Nicollet Mall, Mpls.

Tickets: $102-$30, available at 612-371-5656 or minnesotaorchestra.org

Capsule: A big, booming and beautifully sung “Requiem.”

By Rob Hubbard | Special to the Pioneer Press

May 18, 2019 at 12:29 am

It’s a great month to get to know Giuseppe Verdi, the dominant figure in the history of Italian opera. As Minnesota Opera closes its production of the composer’s most popular opera, “La Traviata,” the Minnesota Orchestra is performing another of his masterpieces, the “Requiem” mass he wrote upon the 1873 death of another giant of Italian culture, the poet and statesman Alessandro Manzoni.

If you have time to catch each this weekend – and, hey, it’s supposed to rain, so why not? – you might just get worn out by all the passion. For Verdi insisted upon that, above all. And Friday evening’s first performance of the “Requiem” at Minneapolis’ Orchestra Hall overflowed with passion. Led by English conductor Edward Gardner, it was a gripping performance, a big, booming look at death that seemed designed both to comfort and to frighten you into repentance.

With the Minnesota Chorale at the top of its game and its voices, this may have been the loudest “Requiem” I’ve ever encountered (and I mean by any composer). Drawing listeners in with its whispering opening, it soon was jarring the audience into alertness with a “Dies Irae” that featured powerful bass drum whacks from principal percussionist Brian Mount, a lovely oboe solo from John Snow, and arias of awe and resignation from bass Eric Owens.

But the most powerful moments came when the audience was summoned into quiet reverence. Such as on an Offertorio with the sweetest of quartets by the four guest vocalists, tenor Rene Barbera upping the operatic ante with a dramatic delivery. The ensuing Sanctus found the Minnesota Chorale (exceptional all evening) doing its best imitation of an opera chorus, especially on the emphatic final notes.

I’d be hard pressed to say who impressed me more, soprano Ailyn Perez or mezzo-soprano Elizabeth DeShong. They wrapped listeners in a blanket of harmony on a duet on the “Agnus Dei,” but that movement showed DeShong at the peak of her powers as she plunged into the depths of her range, sounding very much like a tenor before opening the “Lux Aeterna” with clear, high tones.

Perez then burst forth on the finale, the “Libera Me” that Verdi actually wrote earlier as part of a multi-composer collaborative “Requiem” upon the death of another of opera’s greatest composers, Gioacchino Rossini. When the “Dies Irae” was done offering its shouts of advocacy for fear-based faith, Perez was ready with a transporting, transcendent lullaby. And the Minnesota Chorale – expertly prepared by Kathy Saltzman Romey – seized the standard for drama and passion and ran with it on a final, full-choir fugue.

Verdi’s “Requiem” stands as one of music history’s most powerful hybrids of the sacred and secular, and the enraptured audience greeted its final notes with a lengthy silence suiting the sacred then an extended standing ovation that felt like a cathartic release from the reverie due a very memorable performance.

If You Go

Who: The Minnesota Orchestra with conductor Edward Gardner, soprano Ailyn Perez, mezzo-soprano Elizabeth DeShong, tenor Rene Barbera, bass-baritone Eric Owens and the Minnesota Chorale

What: Giuseppe Verdi’s “Requiem”

When: 8 p.m. Saturday, 2 p.m. Sunday

Where: Orchestra Hall, 1111 Nicollet Mall, Mpls.

Tickets: $102-$30, available at 612-371-5656 or minnesotaorchestra.org

Capsule: A big, booming and beautifully sung “Requiem.”

Review: Mahler – Symphony No. 2 (“Resurrection”) – Osmo Vänskä, Minnesota Orchestra

By Tal Agam, The Classic Review

February 7, 2019

This is the third and, to me, the most successful in Osmo Vänskä’s ongoing Mahler cycle with the Minnesota Orchestra. Together with other ongoing Mahler cycles – namely Adam Fischer’s Dusseldorf series and Daniel Harding newer cycle with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra – we can sense a trend emerges of playing direct, no-nonsense Mahler that frees itself from self indulgence and treating the score as “classically” as possible, letting the music speak for itself.

There is room for diversity of touch nonetheless. Right from the opening bars, where the cellos and basses are calling out the main theme, you can sense the frightening tension in the air, persistent throughout the difficult first movement even on emerging major themes, such as the strings and brass at 06:00. It’s a test for any large orchestra, and the Minnesotas, here and elsewhere in the Symphony, pass it with flying colours.

The Minnesota orchestra was one of the first to record this piece (with Eugene Ormandy in 1935), and their affinity to the music is evident. Listen to the climaxes of the development section of the first movement and see if you can resist it – how the tension forcefully breaks at around 16:00 with no artificial tempo changes, like on Simon Rattle’s otherwise fabulous account with the CBSO. Or the almost static playing before the contrasting, violent bars on 12:15, which demands extreme control from all players.

The second movement is charming without being overly sentimental – Vänskä opts again for the direct approach. Rattle here is almost cynical, while Chailly in his Concertgebouw version more steady, avoiding almost completely from playfulness in the strings. Here, Vänskä allows the section to gleefully play the instructed glissando and sneak-in a smile, as Mahler intended.

You need to be a fine ensemble to play the third, Scherzo movement well, and here it gets an exemplary account by the Minnesotans. Listen to the intricate exchange of all sections at around 03:20 as an example (with some lovely solo Flute playing). It’s a movement of small contrasts, and the group are completely attuned to the subtle changes in colouring required to make it effective.

Simon Rattle famously had Dame Janet Baker for the Mezzo part in his 1990 account, an unforgettable performance that’s very hard to bit. But Sasha Cooke are coming very well close. Her hushed intensity is chilling in the “Urlicht” movement, very nicely accompanied by the solo violin, strings and brass.

The behemoth finale movement is where opinions may split. It’s a well planned, straight to the matter performance that the orchestra and choir manage splendidly. When the “Minnesota Chorale” and soprano Ruby Hughes gets into the picture, they are treated as angelic, stoic participants. This treatment is persistent almost through the end of the movement, where the culmination is an outburst of universal proportions. Klemperer, Chailly and, again, Rattle had a more multicoloured development leading to the climatic final bars, though Boulez had a similar approach in his Vienna Philharmonic version. Arriving to the end of the movement is much more exciting with the contrast of dynamics found here, and you will have to determine if that was worth the hushed suspense.

Like in the previous two volumes in this series (Symphony No. 1, Symphony No. 6), the recording is of demonstrating quality, but in this case the BIS engineers outdid themselves. This is one of the better recorded Seconds on record, perhaps one of the best recorded Mahler Symphonies, on SACD or the compatible two channels CD. With this recording conveniently fitting on a single CD, it’s highly recommended even as a supplement to other versions, some listed below.

Mahler – Symphony No. 2 (“Resurrection”)

Minnesota Orchestra

Osmo Vänskä – Conductor

Ruby Hughes – Soprano

Sasha Cooke – Mezzo

Minnesota Chorale

BIS Records, SACD, CD 2296

By Tal Agam, The Classic Review

February 7, 2019

This is the third and, to me, the most successful in Osmo Vänskä’s ongoing Mahler cycle with the Minnesota Orchestra. Together with other ongoing Mahler cycles – namely Adam Fischer’s Dusseldorf series and Daniel Harding newer cycle with the Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra – we can sense a trend emerges of playing direct, no-nonsense Mahler that frees itself from self indulgence and treating the score as “classically” as possible, letting the music speak for itself.

There is room for diversity of touch nonetheless. Right from the opening bars, where the cellos and basses are calling out the main theme, you can sense the frightening tension in the air, persistent throughout the difficult first movement even on emerging major themes, such as the strings and brass at 06:00. It’s a test for any large orchestra, and the Minnesotas, here and elsewhere in the Symphony, pass it with flying colours.

The Minnesota orchestra was one of the first to record this piece (with Eugene Ormandy in 1935), and their affinity to the music is evident. Listen to the climaxes of the development section of the first movement and see if you can resist it – how the tension forcefully breaks at around 16:00 with no artificial tempo changes, like on Simon Rattle’s otherwise fabulous account with the CBSO. Or the almost static playing before the contrasting, violent bars on 12:15, which demands extreme control from all players.

The second movement is charming without being overly sentimental – Vänskä opts again for the direct approach. Rattle here is almost cynical, while Chailly in his Concertgebouw version more steady, avoiding almost completely from playfulness in the strings. Here, Vänskä allows the section to gleefully play the instructed glissando and sneak-in a smile, as Mahler intended.

You need to be a fine ensemble to play the third, Scherzo movement well, and here it gets an exemplary account by the Minnesotans. Listen to the intricate exchange of all sections at around 03:20 as an example (with some lovely solo Flute playing). It’s a movement of small contrasts, and the group are completely attuned to the subtle changes in colouring required to make it effective.

Simon Rattle famously had Dame Janet Baker for the Mezzo part in his 1990 account, an unforgettable performance that’s very hard to bit. But Sasha Cooke are coming very well close. Her hushed intensity is chilling in the “Urlicht” movement, very nicely accompanied by the solo violin, strings and brass.

The behemoth finale movement is where opinions may split. It’s a well planned, straight to the matter performance that the orchestra and choir manage splendidly. When the “Minnesota Chorale” and soprano Ruby Hughes gets into the picture, they are treated as angelic, stoic participants. This treatment is persistent almost through the end of the movement, where the culmination is an outburst of universal proportions. Klemperer, Chailly and, again, Rattle had a more multicoloured development leading to the climatic final bars, though Boulez had a similar approach in his Vienna Philharmonic version. Arriving to the end of the movement is much more exciting with the contrast of dynamics found here, and you will have to determine if that was worth the hushed suspense.

Like in the previous two volumes in this series (Symphony No. 1, Symphony No. 6), the recording is of demonstrating quality, but in this case the BIS engineers outdid themselves. This is one of the better recorded Seconds on record, perhaps one of the best recorded Mahler Symphonies, on SACD or the compatible two channels CD. With this recording conveniently fitting on a single CD, it’s highly recommended even as a supplement to other versions, some listed below.

Mahler – Symphony No. 2 (“Resurrection”)

Minnesota Orchestra

Osmo Vänskä – Conductor

Ruby Hughes – Soprano

Sasha Cooke – Mezzo

Minnesota Chorale

BIS Records, SACD, CD 2296

New album reviews: Minnesota Orchestra delivers revelatory Mahler's Second Symphony

By Terry Blain Special to the Star Tribune

January 31, 2019 — 3:25pm

Minnesota Orchestra, “Mahler Symphony No. 2, ‘Resurrection’ ” (Bis)

It’s been 84 years since the Minneapolis Symphony became the first U.S. orchestra to record Mahler’s Second Symphony under music director Eugene Ormandy. His tempos in the symphony are among the fastest ever. (The recording is available on YouTube.)

Now known as the Minnesota Orchestra, the group’s current music director, Osmo Vänskä, takes a considerably more expansive view in his new recording of the Second Symphony. This enables exceptionally precise articulation of rhythmic detail in the opening “Funeral Rites” movement, particularly in the scrunching double bass figurations and snapping cello lines that launch Mahler’s sober meditation on mortality and the meaning of human struggle. It’s a dark, introspective reading of the movement. And yet the central cataclysm pulls no punches, with the vertiginous string descent perfectly executed at the movement’s helter-skelter conclusion.

The second and third movements are more relaxed, allowing for plenty of charming, piquant woodwind playing to register.

Mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke’s moving account of the “Urlicht” movement is a brief oasis of calm before the storm of the finale, where the “Resurrection” of the symphony’s title takes place. Vänskä builds this 35-minute movement patiently, but there is no stinting on raw power when the Minnesota Chorale joins for the apocalyptic final moments. The startlingly clear sound captured in Orchestra Hall by Bis’ engineers is a major bonus in this heaven-storming conclusion.

Those who like their Mahler to be constantly teetering on the brink of nervous exhaustion may find parts of this “Resurrection” too slow-burning and even-tempered. Vänskä doesn’t do histrionics. But the sheer range of emotional nuance here is a revelation, just as it was in the orchestra’s previous recordings of Symphonies 5 and 6.

Vänskä will complete the full cycle of Mahler symphonies before stepping down as music director in 2022. With seven more recordings to go, the series is shaping up to be a defining achievement of his Minnesota Orchestra tenure.

By Terry Blain Special to the Star Tribune

January 31, 2019 — 3:25pm

Minnesota Orchestra, “Mahler Symphony No. 2, ‘Resurrection’ ” (Bis)

It’s been 84 years since the Minneapolis Symphony became the first U.S. orchestra to record Mahler’s Second Symphony under music director Eugene Ormandy. His tempos in the symphony are among the fastest ever. (The recording is available on YouTube.)

Now known as the Minnesota Orchestra, the group’s current music director, Osmo Vänskä, takes a considerably more expansive view in his new recording of the Second Symphony. This enables exceptionally precise articulation of rhythmic detail in the opening “Funeral Rites” movement, particularly in the scrunching double bass figurations and snapping cello lines that launch Mahler’s sober meditation on mortality and the meaning of human struggle. It’s a dark, introspective reading of the movement. And yet the central cataclysm pulls no punches, with the vertiginous string descent perfectly executed at the movement’s helter-skelter conclusion.

The second and third movements are more relaxed, allowing for plenty of charming, piquant woodwind playing to register.

Mezzo-soprano Sasha Cooke’s moving account of the “Urlicht” movement is a brief oasis of calm before the storm of the finale, where the “Resurrection” of the symphony’s title takes place. Vänskä builds this 35-minute movement patiently, but there is no stinting on raw power when the Minnesota Chorale joins for the apocalyptic final moments. The startlingly clear sound captured in Orchestra Hall by Bis’ engineers is a major bonus in this heaven-storming conclusion.

Those who like their Mahler to be constantly teetering on the brink of nervous exhaustion may find parts of this “Resurrection” too slow-burning and even-tempered. Vänskä doesn’t do histrionics. But the sheer range of emotional nuance here is a revelation, just as it was in the orchestra’s previous recordings of Symphonies 5 and 6.

Vänskä will complete the full cycle of Mahler symphonies before stepping down as music director in 2022. With seven more recordings to go, the series is shaping up to be a defining achievement of his Minnesota Orchestra tenure.

Joyful Bach heralds the holiday season at the Minnesota OrchestraBaroque specialist Nicholas Kraemer conducts the second part of the 0rchestra's two-year Christmas Oratorio project.

By Terry Blain Special to the Star Tribune

DECEMBER 9, 2018 — 4:41PM

Performing baroque music is not as easy for symphony orchestras as it used to be.

The past four decades have seen a revolution in our appreciation of playing styles in the baroque period, and specialist ensembles using historically accurate instruments have all but cornered the market in Bach, Handel and Vivaldi.

Is it still possible for a modern symphony orchestra to flip back to the baroque manner and make a convincing fist of rivaling the specialists in authenticity?

On Saturday evening, the Minnesota Orchestra proved that it is, in an ebullient performance of Cantatas 4, 5 and 6 from Bach's Christmas Oratorio.

The key ingredient was the presence of Scottish baroque specialist Nicholas Kraemer on the conductor's podium.

His influence was strongly felt in the lean, sprightly performance of Bach's Third Orchestral Suite that opened the concert.

Playing without vibrato — the quivery finger effect employed to richen tone — the violins zipped hyperactively through the infectious dance rhythms of the quicker movements while the famous "Air" lilted along with none of the gooeyness it's sometimes given.

A similar lightness of touch imbued the Christmas Oratorio cantatas that followed after intermission. They told the second part of the Christmas story that was begun in last December's Minnesota Orchestra performances of Cantatas 1-3.

For the Oratorio, the orchestra was pared down to roughly half its normal size and was joined by 49 singers from the Minnesota Chorale, plus four soloists.

Once again the key influencer was conductor Kraemer. Bobbing and jigging on the podium, he coaxed delectably incisive playing from the orchestra and exceptionally vivid singing from the choir.

Bach's sinuous oboe writing plays a prominent part in the Christmas Oratorio, and there was wonderfully fluid playing from principal oboe John Snow and associate principal Kathryn Greenbank.

In an unusual move, they were separated in "Flösst, mein Heiland," a so-called "echo aria" where Greenbank responded to Snow's onstage playing from a position on the first balcony of Orchestra Hall.

Beside her was Minnesota Chorale member Sara Payne, who similarly echoed phrases from soprano Sherezade Panthaki's mellifluous performance of the aria.

The nimble duetting of violinists Susie Park and Peter McGuire was a highlight of the tenor aria "Ich will nur dir zu Ehren leben," where soloist David Portillo did well to etch the coloratura runs at Kraemer's vertiginously zippy tempo.

Portillo was an ardently communicative narrator as the story moved from the christening of Jesus to the Wise Men's visit and Herod's murderous intentions.

Baritone Christopher Edwards briefly lent Herod a touch of pantomime villainy in the recitative "Ziehet hin und forschet fleissig," and sang the bass aria "Erleucht auch meine finstre Sinnen" with impressive solidity.

The English countertenor Robin Blaze made fluid contributions, and conductor Kraemer pulled the various strands of Bach's musical tapestry together in an invigorating performance of the closing chorus "Nun seid ihr wohl gerochen."

It was a joyful peroration, capped by Manny Laureano's exuberant rendition of the preposterously difficult solo that Bach gives his principal trumpet.

Minnesota Orchestra dabbles in new music with fabulous results

By Rob Hubbard | Special to the Pioneer Press

PUBLISHED: September 27, 2018 at 5:06 pm | UPDATED: September 27, 2018 at 5:13 pm

What’s new? At a Minnesota Orchestra concert, usually not much. While music director Osmo Vanska has long spoken of his desire to expose audiences to new music, the programming over at Orchestra Hall can often seem on the conservative side. Familiar favorites tend to be the chief drivers of ticket sales, fresher fare sprinkled in only intermittently.

Rare is the concert at which two of the three pieces were premiered in the last 22 years, but that’s what Vanska and the orchestra are presenting this weekend. There’s the local premiere of a stirring 2014 work by Syrian-American composer Kareem Roustom. And while composer John Adams may not seem “new” this far into his career, his 1996 clarinet concerto, “Gnarly Buttons,” challenges enough of the classical conventions to still sound iconoclastic.

Ah, but it would be particularly daring to have the first weekday “coffee concert” of the season feature nothing for the traditionalists. So “The Planets” was the headliner, Gustav Holst’s very popular orchestral suite receiving an interpretation with all of the desired power, punch and dreaminess. This weekend marks the centennial of the work’s premiere, and Vanska and the orchestra made sure that it was delivered with as much vitality as the younger music on the program.

Roustom’s “Ramal” actually has a lot in common with “The Planets,” what with its powerful percussion, urgent full-orchestra explosions and a lithe ascending line right out of “Mercury.” There’s also a lot of menace afoot, as well as relentlessly turbulent time changes that can make you feel tossed about. But a mystical aura emerges, the absorbing work leaving me intrigued to hear more of Roustom’s creations.

English clarinetist Michael Collins had a lot to do with bringing Adams’ “Gnarly Buttons” into the world. Knowing that the composer was a clarinetist himself, Collins badgered him about writing a clarinet concerto until he finally delivered one that Collins debuted in London. It’s unusual in its instrumentation, featuring an orchestra of only 17 musicians, two of them on electronic keyboards and another on mandolin, banjo and guitar.

Yet the focus never strayed far from Collins’ exceptional musicality. Through many a clearly difficult passage, he was smooth and dexterous, his caramel tone like a steady guide across uncertain ground. The middle movement, “Hoedown,” shared more than just a title with an Aaron Copland piece, as the orchestra two-stepped emphatically beneath Collins’ soaring jazz-flavored lines. The finale, “Put Your Loving Arms Around Me,” was beautiful, with sweet solos by bassoonist Mark Kelley and Julie Gramolini Williams on English horn proving an ideal complement to the urgently pleading melancholy of Collins.

Then it was off to “The Planets,” and it proved quite a rewarding journey. “Mars” felt like one long dark, disturbing eruption that could have been crisper in the concluding hammer blows, but nevertheless brought chills with its full-blown fortissimos. While “Mercury” dragged its winged feet a little too much, the ensuing two movements were both exceptionally well-executed: “Jupiter” had all the buoyancy for which one could wish, while “Saturn” was suffused with a deep emotional complexity, like a troubled prayer, a paradoxical blend of strength and uncertainty. After the mad march of “Uranus,” the wavering unease of “Neptune” soon faded from earshot, the women of the Minnesota Chorale spiriting it away down the balcony hallways, bringing a dreamy conclusion to a concert at which even the old felt new.

By Terry Blain Special to the Star Tribune

DECEMBER 9, 2018 — 4:41PM

Performing baroque music is not as easy for symphony orchestras as it used to be.

The past four decades have seen a revolution in our appreciation of playing styles in the baroque period, and specialist ensembles using historically accurate instruments have all but cornered the market in Bach, Handel and Vivaldi.

Is it still possible for a modern symphony orchestra to flip back to the baroque manner and make a convincing fist of rivaling the specialists in authenticity?

On Saturday evening, the Minnesota Orchestra proved that it is, in an ebullient performance of Cantatas 4, 5 and 6 from Bach's Christmas Oratorio.

The key ingredient was the presence of Scottish baroque specialist Nicholas Kraemer on the conductor's podium.

His influence was strongly felt in the lean, sprightly performance of Bach's Third Orchestral Suite that opened the concert.

Playing without vibrato — the quivery finger effect employed to richen tone — the violins zipped hyperactively through the infectious dance rhythms of the quicker movements while the famous "Air" lilted along with none of the gooeyness it's sometimes given.

A similar lightness of touch imbued the Christmas Oratorio cantatas that followed after intermission. They told the second part of the Christmas story that was begun in last December's Minnesota Orchestra performances of Cantatas 1-3.

For the Oratorio, the orchestra was pared down to roughly half its normal size and was joined by 49 singers from the Minnesota Chorale, plus four soloists.

Once again the key influencer was conductor Kraemer. Bobbing and jigging on the podium, he coaxed delectably incisive playing from the orchestra and exceptionally vivid singing from the choir.

Bach's sinuous oboe writing plays a prominent part in the Christmas Oratorio, and there was wonderfully fluid playing from principal oboe John Snow and associate principal Kathryn Greenbank.

In an unusual move, they were separated in "Flösst, mein Heiland," a so-called "echo aria" where Greenbank responded to Snow's onstage playing from a position on the first balcony of Orchestra Hall.

Beside her was Minnesota Chorale member Sara Payne, who similarly echoed phrases from soprano Sherezade Panthaki's mellifluous performance of the aria.

The nimble duetting of violinists Susie Park and Peter McGuire was a highlight of the tenor aria "Ich will nur dir zu Ehren leben," where soloist David Portillo did well to etch the coloratura runs at Kraemer's vertiginously zippy tempo.

Portillo was an ardently communicative narrator as the story moved from the christening of Jesus to the Wise Men's visit and Herod's murderous intentions.

Baritone Christopher Edwards briefly lent Herod a touch of pantomime villainy in the recitative "Ziehet hin und forschet fleissig," and sang the bass aria "Erleucht auch meine finstre Sinnen" with impressive solidity.

The English countertenor Robin Blaze made fluid contributions, and conductor Kraemer pulled the various strands of Bach's musical tapestry together in an invigorating performance of the closing chorus "Nun seid ihr wohl gerochen."

It was a joyful peroration, capped by Manny Laureano's exuberant rendition of the preposterously difficult solo that Bach gives his principal trumpet.

Minnesota Orchestra dabbles in new music with fabulous results

By Rob Hubbard | Special to the Pioneer Press

PUBLISHED: September 27, 2018 at 5:06 pm | UPDATED: September 27, 2018 at 5:13 pm

What’s new? At a Minnesota Orchestra concert, usually not much. While music director Osmo Vanska has long spoken of his desire to expose audiences to new music, the programming over at Orchestra Hall can often seem on the conservative side. Familiar favorites tend to be the chief drivers of ticket sales, fresher fare sprinkled in only intermittently.

Rare is the concert at which two of the three pieces were premiered in the last 22 years, but that’s what Vanska and the orchestra are presenting this weekend. There’s the local premiere of a stirring 2014 work by Syrian-American composer Kareem Roustom. And while composer John Adams may not seem “new” this far into his career, his 1996 clarinet concerto, “Gnarly Buttons,” challenges enough of the classical conventions to still sound iconoclastic.

Ah, but it would be particularly daring to have the first weekday “coffee concert” of the season feature nothing for the traditionalists. So “The Planets” was the headliner, Gustav Holst’s very popular orchestral suite receiving an interpretation with all of the desired power, punch and dreaminess. This weekend marks the centennial of the work’s premiere, and Vanska and the orchestra made sure that it was delivered with as much vitality as the younger music on the program.

Roustom’s “Ramal” actually has a lot in common with “The Planets,” what with its powerful percussion, urgent full-orchestra explosions and a lithe ascending line right out of “Mercury.” There’s also a lot of menace afoot, as well as relentlessly turbulent time changes that can make you feel tossed about. But a mystical aura emerges, the absorbing work leaving me intrigued to hear more of Roustom’s creations.

English clarinetist Michael Collins had a lot to do with bringing Adams’ “Gnarly Buttons” into the world. Knowing that the composer was a clarinetist himself, Collins badgered him about writing a clarinet concerto until he finally delivered one that Collins debuted in London. It’s unusual in its instrumentation, featuring an orchestra of only 17 musicians, two of them on electronic keyboards and another on mandolin, banjo and guitar.

Yet the focus never strayed far from Collins’ exceptional musicality. Through many a clearly difficult passage, he was smooth and dexterous, his caramel tone like a steady guide across uncertain ground. The middle movement, “Hoedown,” shared more than just a title with an Aaron Copland piece, as the orchestra two-stepped emphatically beneath Collins’ soaring jazz-flavored lines. The finale, “Put Your Loving Arms Around Me,” was beautiful, with sweet solos by bassoonist Mark Kelley and Julie Gramolini Williams on English horn proving an ideal complement to the urgently pleading melancholy of Collins.

Then it was off to “The Planets,” and it proved quite a rewarding journey. “Mars” felt like one long dark, disturbing eruption that could have been crisper in the concluding hammer blows, but nevertheless brought chills with its full-blown fortissimos. While “Mercury” dragged its winged feet a little too much, the ensuing two movements were both exceptionally well-executed: “Jupiter” had all the buoyancy for which one could wish, while “Saturn” was suffused with a deep emotional complexity, like a troubled prayer, a paradoxical blend of strength and uncertainty. After the mad march of “Uranus,” the wavering unease of “Neptune” soon faded from earshot, the women of the Minnesota Chorale spiriting it away down the balcony hallways, bringing a dreamy conclusion to a concert at which even the old felt new.

South African gospel choir brings 'healing' post-apartheid message to Orchestra HallTouring the Midwest this summer, the 29:11 choir found an unlikely partner in Minnesota Orchestra.

By Jenna Ross Star Tribune

JULY 19, 2018 — 1:57PM

Link to article here

By Jenna Ross Star Tribune

JULY 19, 2018 — 1:57PM

Link to article here

Orchestra tribute to Mandela previews South African trip

By Euan Kerr, MPR News

Jul 20, 2018

Link to article here

By Euan Kerr, MPR News

Jul 20, 2018

Link to article here

A No. 9 symphony with special ingredients

By TERRY BLAIN , SPECIAL TO THE STAR TRIBUNE

July 22, 2018 - 4:40 PM

Can music ultimately do anything to cure the ills of humanity and the evils we inflict on one another?

No work in classical music raises that question quite so acutely as Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, the main item in Saturday evening's Minnesota Orchestra program.

Three movements containing a combustible mix of turmoil, agitation and conflicted introspection eventually give way to a finale where joy explodes, and human voices sing a hymn of optimism to the future.

How convincing does that grand conclusion sound in the riven atmosphere of 21st-century America?

On musical terms alone, Saturday evening's performance of the Ninth was a considerable triumph.

Conceived as part of the Minnesota Orchestra's "Music for Mandela" series celebrating the 100th birthday of the great South African statesman, it had power and eloquence in plenty and was played with singular commitment.

Cellos and double basses fizzed with articulate energy in the crucial recitative passages of the finale. In the hyperactive second movement woodwind clucked and chirruped tirelessly, while the slow movement's counter-melody was movingly voiced by the second violin section.

Conductor Osmo Vänskä's Beethoven — taut, propulsive, cuttingly dramatic — is a known quantity from his many Orchestra Hall performances and his Minnesota Orchestra recordings.

On Saturday evening, though, special ingredients were added. A quartet of solo singers from South Africa featured in the finale, adding a unique fervor and authenticity to Friedrich Schiller's words about human solidarity and freedom.

The Minnesota Chorale had also been augmented with singers from The Better Together Choir and 29:11, a vocal ensemble from Cape Town.

They blended seamlessly together in a highly charged account of the famous "Ode to Joy," which ends the symphony.

In the search for textual clarity words were occasionally over-accented in a mannered staccato fashion, with syllables forcibly separated. But overall the chorus's energy was mighty, and some gloriously stirring sounds swept through the auditorium.

The concert opened with "Harmonia Ubuntu," a new work by South African composer Bongani Ndodana-Breen specially written for the Minnesota Orchestra's forthcoming tour of South Africa.

"Ubuntu" is a Nguni Bantu term implying that the integrity and dignity of one human is inextricably linked to that of others. It was a key concept to Nelson Mandela, and a selection of his sayings provided the text for Ndodana-Breen's 12-minute setting.

Mandela's eloquence was offset by a bubblingly eventful score that effectively referenced African rhythms and melodies, and peppered the orchestral textures with a Wasembe rattle and a djembe, two African percussion instruments. Soprano Goitsemang Lehobye was the fervent soloist.

Compared to Beethoven's towering Ninth Symphony, "Harmonia Ubuntu" is a relatively modest, unassuming composition, based on virtually incontestable concepts of simple human decency.

By comparison the Ninth, for all its heaving, convulsing and wrestling with destiny, seemed to tread a more dogged, effortful path toward eventual release and revelation.

Must it necessarily be that way? Ndodana-Breen's short, stimulating work suggested that the path to peace — personal peace, anyway — may not always need to be a titanically protracted process.

Terry Blain is a freelance classical music critic for the Star Tribune. Reach him at [email protected].

By TERRY BLAIN , SPECIAL TO THE STAR TRIBUNE

July 22, 2018 - 4:40 PM

Can music ultimately do anything to cure the ills of humanity and the evils we inflict on one another?

No work in classical music raises that question quite so acutely as Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, the main item in Saturday evening's Minnesota Orchestra program.

Three movements containing a combustible mix of turmoil, agitation and conflicted introspection eventually give way to a finale where joy explodes, and human voices sing a hymn of optimism to the future.

How convincing does that grand conclusion sound in the riven atmosphere of 21st-century America?

On musical terms alone, Saturday evening's performance of the Ninth was a considerable triumph.

Conceived as part of the Minnesota Orchestra's "Music for Mandela" series celebrating the 100th birthday of the great South African statesman, it had power and eloquence in plenty and was played with singular commitment.

Cellos and double basses fizzed with articulate energy in the crucial recitative passages of the finale. In the hyperactive second movement woodwind clucked and chirruped tirelessly, while the slow movement's counter-melody was movingly voiced by the second violin section.

Conductor Osmo Vänskä's Beethoven — taut, propulsive, cuttingly dramatic — is a known quantity from his many Orchestra Hall performances and his Minnesota Orchestra recordings.

On Saturday evening, though, special ingredients were added. A quartet of solo singers from South Africa featured in the finale, adding a unique fervor and authenticity to Friedrich Schiller's words about human solidarity and freedom.

The Minnesota Chorale had also been augmented with singers from The Better Together Choir and 29:11, a vocal ensemble from Cape Town.

They blended seamlessly together in a highly charged account of the famous "Ode to Joy," which ends the symphony.

In the search for textual clarity words were occasionally over-accented in a mannered staccato fashion, with syllables forcibly separated. But overall the chorus's energy was mighty, and some gloriously stirring sounds swept through the auditorium.

The concert opened with "Harmonia Ubuntu," a new work by South African composer Bongani Ndodana-Breen specially written for the Minnesota Orchestra's forthcoming tour of South Africa.

"Ubuntu" is a Nguni Bantu term implying that the integrity and dignity of one human is inextricably linked to that of others. It was a key concept to Nelson Mandela, and a selection of his sayings provided the text for Ndodana-Breen's 12-minute setting.

Mandela's eloquence was offset by a bubblingly eventful score that effectively referenced African rhythms and melodies, and peppered the orchestral textures with a Wasembe rattle and a djembe, two African percussion instruments. Soprano Goitsemang Lehobye was the fervent soloist.

Compared to Beethoven's towering Ninth Symphony, "Harmonia Ubuntu" is a relatively modest, unassuming composition, based on virtually incontestable concepts of simple human decency.

By comparison the Ninth, for all its heaving, convulsing and wrestling with destiny, seemed to tread a more dogged, effortful path toward eventual release and revelation.

Must it necessarily be that way? Ndodana-Breen's short, stimulating work suggested that the path to peace — personal peace, anyway — may not always need to be a titanically protracted process.

Terry Blain is a freelance classical music critic for the Star Tribune. Reach him at [email protected].

A praiseworthy Bernstein Chichester Psalms from the Minnesota Orchestra

By Phillip Nones, 05 June 2018, www.bachtrack.com

Reviewed at Orchestra Hall, Minneapolis on 1 June 2018

In this year of the Bernstein centenary, there’s no dearth of performances of the iconic composer’s music – at least here in America. This Minnesota Orchestraconcert led by Andrew Litton was no exception, with half of the program being taken up by two Bernstein compositions. Fancy Free is an early Bernstein creation, dating from 1944 when the composer was just 26 years old. Yet it’s a highly representative work – indeed, one of the best examples of Bernstein’s use of dance rhythms and jazz idioms in his music.

Most probably, US audiences have had more opportunities to hear the piece in concert in 2018 than ever before. I reviewed another Fancy Free performance earlier this year, presented by the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra conducted by Fabien Gabel. Compared to that performance – and indeed to others that I’ve heard – I found the Minnesota outing curiously uninvolving. There was plenty of rhythmic bite, but little discernible differentiation in dynamic range throughout the 25-minute suite of dances.

Instrumental ensemble was fine and the various solo turns were handled deftly, but the end result was a rather characterless performance. Some passages seemed stuck on one volume level (“loud”), which in the end made the presentation sound – dare I say it – rather dull. It surprised me. For the other works on the program, the orchestra was joined by a well-prepped Minnesota Chorale for Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms and Sir William Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast. The Walton piece was never supposed to become famous. It was a one-off creation for the 1931 Leeds Triennial Music Festival, and it was the conductor Sir Thomas Beecham who advised Walton that he might as well use all of the extensive choral and instrumental forces at his disposal (including antiphonal trumpets) in his composition because “you’ll never hear the thing again.” Perhaps the composer was as surprised as anyone that Belshazzar’s Feast went on to become a staple of the choral repertoire, beloved by singers, musicians and audiences alike.

The Minnesota Chorale’s presentation was highly effective, providing dramatic contrasts in the beginning sections (“Thus Spake Isaiah” and “If I Forget Thee”) – then switching gears in their colorful depiction of the grand feast, the king’s murder, and the rejoicing of the Hebrews. Christopher Maltman’s baritone solo passages were persuasive and colorful in the opening sections, but when he decided to become more stentorian in his declamatory solo introducing the feast, his voicing took on an unpleasant tone with excessive vibrato (and intonation approximate at best). It was a miscalculation. In the grand celebration that followed (“Praise Ye the God of Gold”), the forward propulsion that is innate to this music somehow lagged. Litton’s somewhat stolid tempo may have been partially the cause, but I think it was also the lack of dynamic contrasts, which are so critical to making the music soar even in its loudest and most forceful passages. That didn’t happen tonight; instead, I found my mind wandering when it should have been fully engaged.

One other aspect of the performance, which had little to do with the music we were hearing, was an intrusion nevertheless. The way the percussion instruments were arrayed on the stage had one of the players frantically racing back and forth between stations. It was the kind of visual distraction that couldn’t help but get in the way of fuller enjoyment of the concert.

Happily, the choral and orchestral forces were brought together in a second piece which turned out to be the pinnacle of the evening: Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms. Reportedly, Bernstein wanted this music to be “forthright, songful, rhythmic and youthful”, in which he clearly succeeded. Similarly, the members of the Minnesota Chorale succeeded beyond measure in bringing forth those very qualities as part of their exemplary interpretation.

At the outset, the Chorale voiced the words of Psalm 108 with crisp diction and incisive singing. The contrasting 23rd Psalm was beautifully presented by the chorus and orchestra, ably assisted by boy soprano Kevin Torstenson, who was a last-minute replacement for an indisposed Nick Cecchi. The third and final part of Chichester began with an elegiac introduction played with subdued passion by the orchestra’s string section, leading to a quietly intense setting of Psalm 131. The quartet of cellos called for in this section were gorgeously silken, as were the unaccompanied voices intoning the verse from Psalm 133 to end the piece.

I often smile at the little ditty that Bernstein wrote once about his Chichester Psalms: “These Psalms are a simple and modest affair – tonal and tuneful and somewhat square.” In tonight’s performance, “tonal and tuneful and somewhat square” turned out to be the winning ticket, making Chichester the crowning achievement of the evening’s concert.

By Phillip Nones, 05 June 2018, www.bachtrack.com

Reviewed at Orchestra Hall, Minneapolis on 1 June 2018

In this year of the Bernstein centenary, there’s no dearth of performances of the iconic composer’s music – at least here in America. This Minnesota Orchestraconcert led by Andrew Litton was no exception, with half of the program being taken up by two Bernstein compositions. Fancy Free is an early Bernstein creation, dating from 1944 when the composer was just 26 years old. Yet it’s a highly representative work – indeed, one of the best examples of Bernstein’s use of dance rhythms and jazz idioms in his music.

Most probably, US audiences have had more opportunities to hear the piece in concert in 2018 than ever before. I reviewed another Fancy Free performance earlier this year, presented by the Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra conducted by Fabien Gabel. Compared to that performance – and indeed to others that I’ve heard – I found the Minnesota outing curiously uninvolving. There was plenty of rhythmic bite, but little discernible differentiation in dynamic range throughout the 25-minute suite of dances.

Instrumental ensemble was fine and the various solo turns were handled deftly, but the end result was a rather characterless performance. Some passages seemed stuck on one volume level (“loud”), which in the end made the presentation sound – dare I say it – rather dull. It surprised me. For the other works on the program, the orchestra was joined by a well-prepped Minnesota Chorale for Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms and Sir William Walton’s Belshazzar’s Feast. The Walton piece was never supposed to become famous. It was a one-off creation for the 1931 Leeds Triennial Music Festival, and it was the conductor Sir Thomas Beecham who advised Walton that he might as well use all of the extensive choral and instrumental forces at his disposal (including antiphonal trumpets) in his composition because “you’ll never hear the thing again.” Perhaps the composer was as surprised as anyone that Belshazzar’s Feast went on to become a staple of the choral repertoire, beloved by singers, musicians and audiences alike.

The Minnesota Chorale’s presentation was highly effective, providing dramatic contrasts in the beginning sections (“Thus Spake Isaiah” and “If I Forget Thee”) – then switching gears in their colorful depiction of the grand feast, the king’s murder, and the rejoicing of the Hebrews. Christopher Maltman’s baritone solo passages were persuasive and colorful in the opening sections, but when he decided to become more stentorian in his declamatory solo introducing the feast, his voicing took on an unpleasant tone with excessive vibrato (and intonation approximate at best). It was a miscalculation. In the grand celebration that followed (“Praise Ye the God of Gold”), the forward propulsion that is innate to this music somehow lagged. Litton’s somewhat stolid tempo may have been partially the cause, but I think it was also the lack of dynamic contrasts, which are so critical to making the music soar even in its loudest and most forceful passages. That didn’t happen tonight; instead, I found my mind wandering when it should have been fully engaged.

One other aspect of the performance, which had little to do with the music we were hearing, was an intrusion nevertheless. The way the percussion instruments were arrayed on the stage had one of the players frantically racing back and forth between stations. It was the kind of visual distraction that couldn’t help but get in the way of fuller enjoyment of the concert.

Happily, the choral and orchestral forces were brought together in a second piece which turned out to be the pinnacle of the evening: Bernstein’s Chichester Psalms. Reportedly, Bernstein wanted this music to be “forthright, songful, rhythmic and youthful”, in which he clearly succeeded. Similarly, the members of the Minnesota Chorale succeeded beyond measure in bringing forth those very qualities as part of their exemplary interpretation.

At the outset, the Chorale voiced the words of Psalm 108 with crisp diction and incisive singing. The contrasting 23rd Psalm was beautifully presented by the chorus and orchestra, ably assisted by boy soprano Kevin Torstenson, who was a last-minute replacement for an indisposed Nick Cecchi. The third and final part of Chichester began with an elegiac introduction played with subdued passion by the orchestra’s string section, leading to a quietly intense setting of Psalm 131. The quartet of cellos called for in this section were gorgeously silken, as were the unaccompanied voices intoning the verse from Psalm 133 to end the piece.

I often smile at the little ditty that Bernstein wrote once about his Chichester Psalms: “These Psalms are a simple and modest affair – tonal and tuneful and somewhat square.” In tonight’s performance, “tonal and tuneful and somewhat square” turned out to be the winning ticket, making Chichester the crowning achievement of the evening’s concert.

Conductor Andrew Litton leads the Minnesota Orchestra and Minnesota Chorale in Bernstein and Walton this weekend.

By Rob Hubbard | Special to the Pioneer Press

PUBLISHED: June 2, 2018 at 2:07 am | UPDATED: June 2, 2018 at 4:46 pm

There’s a lot of Bernstein about this year. Many a purveyor of classical music and musical theater is finding a way to pay tribute to composer Leonard Bernstein on the 100th anniversary of his birth. The Guthrie Theater’s doing “West Side Story” this summer, and the Minnesota Orchestra has already presented the film version (with live orchestra) and other works. Meanwhile, others are delving into his chamber music, choral pieces and other fare.

But I finally encountered the Bernstein tribute I didn’t know I needed on Friday night at Minneapolis’ Orchestra Hall. Conductor Andrew Litton and the Minnesota Orchestra devoted half of the program to Bernstein, and it was his “Chichester Psalms” that struck me strongest, the Minnesota Chorale offering a Bernstein gift that you may have overlooked: his way with choral harmony. It’s a very moving 1965 setting of psalm texts, and the choir and orchestra made them simply beautiful.

Now, granted, that work wouldn’t even be called the “magnum opus” of the program. That would be William Walton’s “Belshazzar’s Feast” and the orchestra and choir made that 20th-century English cantata – also based in the Hebrew Bible or Old Testament – a very exciting musical experience. It was bold and brassy, given high drama worthy of a Cecil B. DeMille epic. And, as on the “Chichester Psalms,” the orchestra and choir were equally outstanding.

It would be understandable if you saw Andrew Litton’s name and asked, “Is it Sommerfest already?” But Litton concluded his 15-year tenure as artistic director of that summer music festival in 2017. A key difference between that different-program-every-night approach and this week’s subscription concerts is rehearsal time: Litton and the musicians are able to more fully shape their interpretations of Bernstein and Walton.

And that showed from the concert’s start Friday night, as Litton led the orchestra in the complete ballet music from “Fancy Free,” which the young Bernstein composed in 1944. If a dance-filled story of three sailors looking for love on leave sounds like the musical, “On the Town,” know that this ballet inspired that stage musical. (The film kept the story, but jettisoned Bernstein’s music… unfortunately, for much of it is wonderful.) The Minnesota Orchestra doesn’t always swing as much as it could, but it did here, admirably negotiating the score’s rhythmic puzzles and mood shifts from garrulous to steamy to hyperactive to melancholy.

Maybe the reason that the “Chichester Psalms” made such an impression upon me is that it doesn’t hold a trace of the quest for commercial success that drove Bernstein’s greatest hits. Written for an English choral festival, the piece feels like a deeper undertaking than any of his other works for the theater or concert hall, a setting of psalm texts sung in the Hebrew that the composer learned in his youth. And youth plays into the work, for he insisted that the lone soloist be a boy soprano singing Psalm 23 (“The Lord is my shepherd”). Yet it’s the work’s final movement that made me feel as if Bernstein were reaching into hearts from beyond the grave, a soft yet urgent plea for peace.

Walton’s “Belshazzar’s Feast” was quite the dynamic contrast, full of explosive exclamations and stirring exchanges between orchestra, choir and baritone Christopher Maltman, whose powerful voice delivered much of the tale of bawdy Babylon’s fall. If the “Chichester Psalms” asked for subtlety from the musicians, “Belshazzar” requested a forthrightness bordering on bombast. Both works made a joyful noise (and referenced one), Walton’s work climaxing with trumpets in the balconies and a full-throated “Alleluia” that I would heartily echo.

By Rob Hubbard | Special to the Pioneer Press

PUBLISHED: June 2, 2018 at 2:07 am | UPDATED: June 2, 2018 at 4:46 pm

There’s a lot of Bernstein about this year. Many a purveyor of classical music and musical theater is finding a way to pay tribute to composer Leonard Bernstein on the 100th anniversary of his birth. The Guthrie Theater’s doing “West Side Story” this summer, and the Minnesota Orchestra has already presented the film version (with live orchestra) and other works. Meanwhile, others are delving into his chamber music, choral pieces and other fare.

But I finally encountered the Bernstein tribute I didn’t know I needed on Friday night at Minneapolis’ Orchestra Hall. Conductor Andrew Litton and the Minnesota Orchestra devoted half of the program to Bernstein, and it was his “Chichester Psalms” that struck me strongest, the Minnesota Chorale offering a Bernstein gift that you may have overlooked: his way with choral harmony. It’s a very moving 1965 setting of psalm texts, and the choir and orchestra made them simply beautiful.